nathaniel sackett

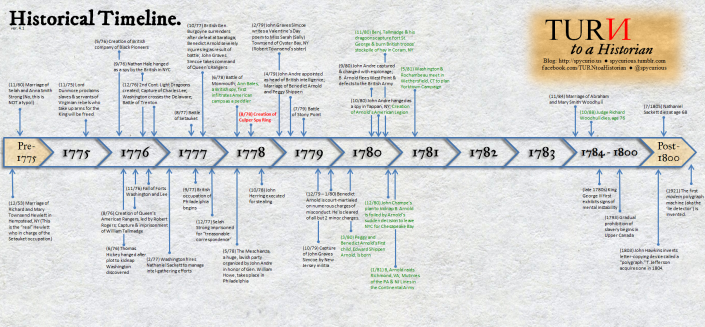

TURN Historical Timeline updated for Season 4 (Part One)

As the TURN: Washington’s Spies storyline hurls itself toward the end of the Revolutionary War, its writers seem determined to name-drop as many minor characters and events as they can in the show’s final episodes. (Perhaps they’re making up for lost time, as one of the most common viewer complaints about Season 1 was that it didn’t contain enough espionage or war-related action).

As a result, the Historical Timeline is bigger than ever — with ample room for the tsunami of names and dates that the last two episodes of the series are sure to generate. Even though there’s only two episodes left, there’s a lot of ground to cover if the writers plan to wrap up the stories of all the characters tied to the Culper Ring — so, who knows? The next Timeline update might be even larger than this one!

All “new” events — that is, all events referenced in Season 4 thus far — are in green text. Click on the image below to enlarge. You can also visit the blog’s Timeline page to see a chronological list of all events shown on the Timeline with plenty of links to further reading. As always, if there’s an event that is referenced in the show that you don’t see on the Timeline, let me know and I’ll add it in during the next update!

In general, there’s been less deviation from historical chronology in Season 4 of TURN than there has been in the previous three seasons. Some notable differences between TURN and the factual historical timeline include:

- Peggy and Benedict Arnold’s first child was born in March 1780, meaning that Peggy was nursing a six-month-old infant at the time Benedict fled West Point after his treason was discovered.

- Ann Bates was active as a spy (as a peddler in disguise) from June 1778 through May 1780 — a full year before Washington and Rochambeau began planning the Yorktown Campaign.

- For a nice recap of how TURN combined elements of both the Pennsylvania and New Jersey Line mutinies, which were technically two separate events that took place in January 1780, read J.L. Bell’s review of Season 4 Episode 4, “Nightmare.”

- Just like poor Nathaniel Sackett, Judge Woodhull was killed off long before his time in the fictional universe of TURN. Happily, he not only survived the Revolutionary War, but lived long enough to see his son Abraham get married (which also happened after the war was over).

And with that, it’s off to the races as the penultimate episode airs later tonight (9:00pm Eastern time). See you on Twitter tonight, TURNcoats! And don’t worry — although the crazy summer schedule of Season 4 has thrown off the regular posting rhythm ’round these parts, the blog posts and updates will keep rolling out long after the August 12th finale, so stick around!

-RS

Spycraft in TURN: Nathaniel Sackett’s Anachronistic Gadgets (Or: What year is this again?)

Here’s a rhetorical question for you, fellow TURNcoats: Why make a show about Revolutionary War espionage when the spy technology you focus on most is from the 15th, 19th, and even 20th centuries?

You might reply: “Well… because it’s fun. And I can make a cool story out of it.” Great! That’s certainly a fair answer. But in that case — why would you try so hard to convince people that your story is fact-based and “authentic” to the 18th century when that argument is pretty much impossible to support?

I found myself asking these very questions while updating the TURN Historical Timeline to reflect the events portrayed in the last few episodes (thought admittedly not for the first time). We had to reconfigure the location of a few things on the Timeline this week in order to fit in more events at the tail end of it – two which occurred in the 19th century and one that even occurred in the early 20th century, well over 100 years after the end of the Revolutionary War! (You can check out the updated version by clicking on the image below, or visiting the Timeline page for additional information.)

“Nice gadgets you have there. But what happened to the 18th century?”

Historians might ask themselves “What year is this supposed to be again?” while watching TURN for a multitude of reasons (issues with clothing, uniforms, other material culture, language, false historical claims, premature character deaths, etc.) — but for this post, we’re focusing on intelligence history, which is what TURN is supposed to be about. Heck, they even changed the official name of the show after Season 1 to clarify that the show is all about “Washington’s Spies”! Thus far, however, TURN’s treatment of Revolutionary War espionage has been erratic at best.

When it comes to spycraft, Season 1 of TURN definitely started off in the right place, featuring period-correct techniques like Cardan grilles and even the original Culper Spy code — exciting, cunning, and historically-accurate stuff! And TURN’s opening credits have been teasing us for over a year with a silhouette of the Turtle, the world’s first military submarine that actually debuted in 1776. (I’m saving a fuller discussion about the Turtle for later, in hopes that we’ll see it in the show soon.)

We’ve also seen the occasional use of invisible inks (or, as they were often called in the 18th century, “sympathetic stains”) – but even that element of Revolutionary spycraft has been given a strange and uneven treatment in TURN. Instead of focusing on the state-of-the-art chemical compound developed by James Jay for the use of Washington’s spies (which is a fascinating true story) the show seems near-obsessed with the novelty of writing invisible messages through the shells of hard-boiled eggs – a centuries-old technique that the Culper Spy Ring never actually used.

In his book Invisible Ink: Spycraft of the American Revolution, John Nagy sums up the origins and functionality of the “egg method” we’ve seen so often in TURN:

In the fifteenth century Italian

scientist Giovanni Porta described how to conceal a message in a hard-boiled egg. An ink is made with an ounce of alum and a pint of vinegar. This special penetrating ink is then used to write on the hard boiled egg shell. The solution penetrates the shell leaving no visible trace and is deposited on the surface of the hardened egg. When the shell is removed, the message can be read. (Invisible Ink, p. 7)

It’s a fascinating technique, and leads to quite a few dramatic (and highly amusing) moments in TURN. The only problem is that, according to the historical record, the Culper spies ever used the egg method — and neither did anyone else in the Revolutionary War, for that matter. There is no record of the technique ever being used by either side.

But if Season 1’s use of Revolutionary War spycraft was fairly solid with a few aberrations, Season 2 is just the opposite — with anachronistic techniques far outnumbering the period-correct ones thus far. Nathaniel Sackett’s “spy laboratory,” with its vials and beakers and fantastical super-weapons, is better suited to a steampunk movie than anything resembling the 18th century. (So is the bearded, blunderbuss-carrying, leather-trenchcoat-wearing version of Caleb Brewster, but that’s a whole other post in itself.)

Now, in terms of making a storyline easy to follow, creating a centralized place as a sort of “spy headquarters” might make sense for a work of historical fiction, even if such a place never actually existed. However, nearly everything we’ve seen featured in Nathaniel Sackett’s anachronistic “spy lab” is from the 19th century – or even later. Besides the never-actually-used egg method discussed above, both of the most prominent examples of spy technology showcased in Season 2 so far were both invented long after the American Revolution was over:

1) John Hawkins’ letter-copying machine, or “polygraph,”  which Tallmadge uses to forge a letter in the episode “False Flag.” Patented in 1803 – twenty years after the end of the Revolution – Hawkins’ machine greatly facilitated the arduous tasking of letter copying. Thomas Jefferson bought one for himself which visitors can still see today at Monticello. Jefferson was a huge fan of the innovative device, and he later said “the use of the polygraph has spoiled me for the old copying press the copies of which are hardly ever legible.” Before the late 19th century, the term “polygraph” was used to described copying devices like this one. You can read more about Hawkins’ polygraph machine in the Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia.

which Tallmadge uses to forge a letter in the episode “False Flag.” Patented in 1803 – twenty years after the end of the Revolution – Hawkins’ machine greatly facilitated the arduous tasking of letter copying. Thomas Jefferson bought one for himself which visitors can still see today at Monticello. Jefferson was a huge fan of the innovative device, and he later said “the use of the polygraph has spoiled me for the old copying press the copies of which are hardly ever legible.” Before the late 19th century, the term “polygraph” was used to described copying devices like this one. You can read more about Hawkins’ polygraph machine in the Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia.

2) Nathaniel Sackett’s bogus “lie detector” from the episode “Sealed Fate.” I’m not even sure where to begin with this one. For starters, the modern-day polygraph or “lie detector” wasn’t invented until 1923. Italian scientists (who always seem to be at the forefront of spy technology!) started experimenting with measuring physical responses to lying and truth-telling in the late 1870s – which is still 100 years ahead of TURN’s Revolutionary War storyline. TURN’s version of Nathaniel Sackett must have been a true visionary to be able to throw together a prototype of a machine that wasn’t invented until after World War I. Too bad they decided to kill him off thirty years too early in the show. (Or as another viewer said on Twitter: “If only Sackett had lived. The Continental Army may have had tanks by 1781.”

Even if the bizarre machine wasn’t supposed to be taken seriously, Tallmadge’s use of the faux-polygraph as a form of psychological torture in order to extract information is just as historically inaccurate as the machine itself. We’ve covered the topic of torture extensively here in the blog. If you haven’t read the original post, you should, but to make a long story short: Torture was very rarely used as a means to obtain intelligence in the Revolutionary War, in sharp contrast to what we’ve seen portrayed multiple times in TURN.

Now here’s the frustrating thing: The American Revolution DID have plenty of awesome and innovative spycraft of its own – from creative concealment techniques to cyphers, masks and grilles, invisible ink, flamboyant messengers, and even “strange but true” experimental technology like the Turtle. It’s not as if the writers of TURN are starved for real-life examples of 18th century innovation. (I’d like to point out that John Nagy’s book referenced above, which only deals with Revolutionary-era spycraft, is nearly 400 pages long. There’s a LOT of historical material to work with.) It’s disappointing to see a show that was supposed to focus exclusively on Revolutionary War espionage morph into an anachronistic drama that has little regard for the time period in which it takes place — especially when the series started off on a much stronger footing.

Returning to our updated timeline: Season 2 seems to have left the 18th century behind in several other ways as well. In addition to using “futuristic” spy technology, we’ve recently seen real historical characters killed off decades too early and King George III turned into a drooling, raving lunatic long before his first recorded bouts of mental instability. For all you viewers who were devastated at Nathaniel Sackett’s untimely death, you’ll be pleased to know that in reality, Sackett survived the Revolution intact, dying at age 68 in 1805. Indeed, he served the contributed to the cause of American independence in a number of different capacities — in addition to his covert operations for Washington, he also was an active member of the Congressional Committee of Safety and later served as a sutler (merchant) for the Continental Army.

Like we’ve said many times before, here at the blog we understand the necessity of shuffling around some historical events in order to present a dramatic narrative that’s easier to follow. Plenty of events in TURN are off by only a year or two, which is reasonable by most people’s definitions. But as the episodes roll on, we’re finding we need to plot more and more events at the extremes of the historical timeline — including major events that play a central role in TURN’s unfolding storylines. Regarding intelligence history — which is what the entire show is supposed to be about — the most prominently-featured spy techniques of TURN’s second season were never used in the Revolutionary War at all. The evidence strongly suggests that the writers and producers of TURN are increasing their disregard for the historical record as Season 2 progresses. That’s not to say, of course, that there’s no hope left — indeed, my personal favorite episode of the entire series, chock-full of excellent historically-informed intrigue, occurred after the halfway point of the first season. (Episode 6 of Season 1, “Mr. Culpepper,” for the record.) So while the show is in the midst of a rather disappointing trend, there’s still plenty of time left in Season 2 for things to turn a corner. Here’s hoping the 18th century makes a comeback, and soon!

-RS