Simcoe Takes Command! Reforming the Queen’s Rangers in 1777

At the end of TURN’s first season, actor Samuel Roukin hinted that Season Two would only be bigger and better for John Graves Simcoe and the Queen’s Rangers. Revolutionary War historians immediately assumed this likely meant that he would take command of the Queen’s Rangers – but then again, given the many liberties the show had already taken with the character of Simcoe, nobody could be certain. Sure enough, by the end of Episode 2 in the second season, Simcoe had undergone quite the dramatic change as commander of the Queen’s Rangers – emphasis, of course, on “dramatic.” For more illuminating detail on this fateful TURN of events, we once again turn to Loyalist expert Todd Braisted. Enjoy! -RS

Did Simcoe’s takeover of the Rangers really occur as portrayed on TURN, with a psychotic madman scalping and shooting one of his own men to get some street cred with a band of ruffians who look better suited to fight the Pirates of the Caribbean? If you have been following our posts for the past year, you likely know the answer – but before we discuss Simcoe’s entrance, let’s take a step back and examine exactly why (a beardless) Robert Rogers actually lost command of the Rangers in the first place.

When the corps was first raised in the summer and fall of 1776, Rogers appointed a number of rather interesting men as his officers. Some of these men were “mechanics,” (tradesmen), while “others had kept Publick Houses and one or two had even kept Bawdy Houses in the city of New York.” A “bawdy house” was an 18th Century term for a brothel – the keepers of which were generally not considered worthy to be officers in His Majesty’s Service. Some of Rogers’ appointed officers were accused of “scandalous and ungentlemanlike behaviour” in robbing and plundering the inhabitants, along with defrauding soldiers of their enlistment bounty money. The rank and file of the unit were a mix of Loyalists from the greater New York City area along with rebel deserters and prisoners of war. One company of the Rangers, under Captain Robert Cook of Massachusetts, appears to have been composed primarily or even entirely of blacks. The composition of the Queen’s Rangers under Robert Rogers was unconventional, to say the least. Before too long, the unit found itself a target for reformation and reorganization.

The first step to reforming the corps was to remove Rogers from command, which was effected on 30 January 1777 when Major Christopher French of the British 22nd Regiment of Foot was placed in charge of the corps. French, a former hero of the French and Indian War, was ordered to report to the newly appointed Inspector General of Provincial Forces, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Innes, whose first piece of official business was to examine the accounts of the Queen’s Rangers. For the next two months Innes reviewed all the financial paperwork of the unit, as well as the state of the different companies and the conduct of the officers. By the middle of March 1777, Innes began to make his mark on the Provincial Forces, attempting to mold them into the same image as regular (and more respectable) British corps. With the approval of Sir William Howe, British commander-in-chief, Innes ordered all the corps to discharge any blacks, mulattoes, Indians, sailors or other “improper persons.” Blacks afterwards would not serve in the Provincial Forces (other than the unarmed corps of Black Pioneers) except as pioneers, drummers, trumpeters and musicians. They definitely would not be made second in command of the Queens Rangers…

Once Innes had accomplished this piece of business, he was ready to lay the hammer down on the officers of the Queen’s Rangers. The day after Innes had requested Howe’s permission to discharge the black Loyalists from the units, Rogers was ordered to present a list of all his officers, and those who had received warrants to recruit men. Of the thirty-three officers examined Innes determined only seven were worthy of continuing in the corps (which would almost immediately be diminished by one when Captain Job Williams murdered Lieutenant Peter Augustus Taylor). Rogers and the remaining twenty-six officers would all be stripped of their commissions (without benefit of any courts martial, a legal requirement for which Howe and Innes would be sued after the war) and set at liberty to pursue new careers. To be fair, some of these men were guilty of nothing more than serving in the wrong corps at the wrong time. Seven of these dismissed officers soon found their way into other Provincial units and served with distinction for the remainder of the war. A nucleus of the dismissed officers would become a major pain in the butt for any British officer or government official willing to listen to them, spending the remainder of the war constantly applying to have their commissions – and all their back pay – restored.

![Gen[1]._Sir_William_Howe](https://spycurious.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/gen1-_sir_william_howe.jpg?w=250&h=327)

It was Wemyss who really put the discipline in the corps that it would display later that summer of 1777 when it was a part of the Philadelphia Campaign. That discipline would be put to the test on September 11th, 1777, when the Queen’s Rangers was ordered to assault across the Brandywine Creek, in the face of close range Continental Artillery. As a part of the force under Hessian General Knyphausen, the corps boldly charged the artillery and helped win the day for the British. As The Pennsylvania Ledger later reported:

“No regiment in the army has gained more honor in this campaign than the Queen’s Rangers; they have been engaged in every principal service and behaved nobly; indeed most of the officers have been wounded since we took the field in Pennsylvania. General Knyphausen, after the action of the 11th September at Brandywine, despatched an aide-de-camp to General Howe with an account of it. What he said concerning it was short but to the purpose. “Tell the General,” says he, “I must be silent as to the behaviour of the Rangers, for I want even words to express my own astonishment to give him an idea of it.”

The following appeared in orders: “The Commander in Chief desires to convey to the officers and men of the Queen’s Rangers his approbation and acknowledgement for their spirited and gallant behaviour in the engagement of the 11th inst. and to assure them how well he is satisfied with their distinguished conduct on that day. His excellency only regrets their having suffered so much in the gallant execution of their duty.”

That one day would be the bloodiest in the history of the corps, with seventy-three of their men (including eleven officers) killed and wounded. (Among them was Captain Job Williams, who perhaps became reacquainted with Lieutenant Taylor in the afterlife.) This was probably a quarter of the Rangers who fought in the battle, and at least a third of the officers.

Elsewhere on the same battlefield, a red-coated British Grenadier officer, Captain John Graves Simcoe, was also wounded. It would be his last battle as a red coat.

On October 15th, 1777 Captain Simcoe was on duty “at the Batteries on Mud Island” in the Delaware River when he received orders to take command of the Queen’s Rangers. The twenty-five year old Englishman arrived in the City of Philadelphia the following day, where he joined the corps. The Rangers at that time were indeed in the city, not in the woods, and needless to say, Simcoe did not scalp or shoot any of them upon his arrival. They also did not have any palpable disdain for regular British officers, having served commendably under their command for the past nine months. It should be pointed out that, contrary to what we’ve seen on TURN, there were more than just two dozen badly-dressed men in the regiment. The strength of the corps was about 425 enlisted men, wounded and absent included.

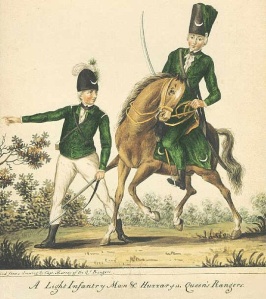

Simcoe would model the Rangers more or less on British lines, at least at first. The corps would have a grenadier and light infantry company, but also an “eleventh [company] was formed of Highlanders” who “were furnished with the Highland dress, and their national piper, and were posted on the left flank of the regiment.” By the end of November, Simcoe would mount a few of his men as “hussars” or light cavalry as well as arm a few of the men with rifles, the weapon so often associated with Washington’s frontiersmen. The dress of the corps at this time was almost certainly the same as the other Provincial units of the time — green coats faced white with hats — not the distinctive dress later associated with the Rangers and which is now shown in the series. That uniform would be first worn in late February 1780, after the corps received the honor of being awarded the name of 1st American Regiment — an appellation still used by the modern-day Queen’s Rangers, who now serve as an Armoured Corps of the Royal Canadian Army. The real Rangers under the real Simcoe would be very active around Philadelphia through the winter of 1780. It will be interesting to see what the showrunners decide to do with that historical information. If we are to believe Mr. Roukin, only bigger and better things lie ahead for Simcoe and the Rangers…

Finally: Many readers have also asked about the significance of the crescent moon on the Queen’s Rangers uniforms. Again, there is no evidence this symbol (or “device”) was used before 1780 which is when the Rangers received their famous and distinct uniforms pictured above. As for the history of the device, this is what the modern-day Queen’s Rangers have to say about it:

During the American Revolution, and later during service in Upper Canada, Rangers wore on their headdress a crescent moon, symbol of Diana, Roman goddess of the hunt. As a reminder of this, the symbol is emblazoned on the Regimental guidon. The crescent moon has taken on a mythology of its own among members of the Regiment, and remains a popular unofficial symbol to this day. It is often found sewn discreetly to the back of bush hats, or perhaps more recently attached with velcro to body armour. Rumour has it the Ranger crescent has been spotted (or, ideally, not spotted) as far afield as Bosnia, Afghanistan, Cyprus, and many other places in between.

—————————————————————————————-

Todd W. Braisted is an author and researcher of Loyalist military studies. His primary focus is on Loyalist military personnel, infrastructure and campaigns throughout North America. Since 1979, Braisted has amassed and transcribed over 40,000 pages of Loyalist and related material from archives and private collections around the world. He has authored numerous journal articles and books, as well as appearing as a guest historian on episodes of Who Do You Think You Are? (CBC) and History Detectives (PBS). He is the creator of the Online Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies (royalprovincial.com), the largest website dedicated to the subject. Braisted is a Fellow in the Company of Military Historians, Honorary Vice President of the United Empire Loyalist Association of Canada, and a past-president of the Bergen County Historical Society. His newest book, Grand Forage 1778: The Revolutionary War’s Forgotten Campaign, will be published in 2016.